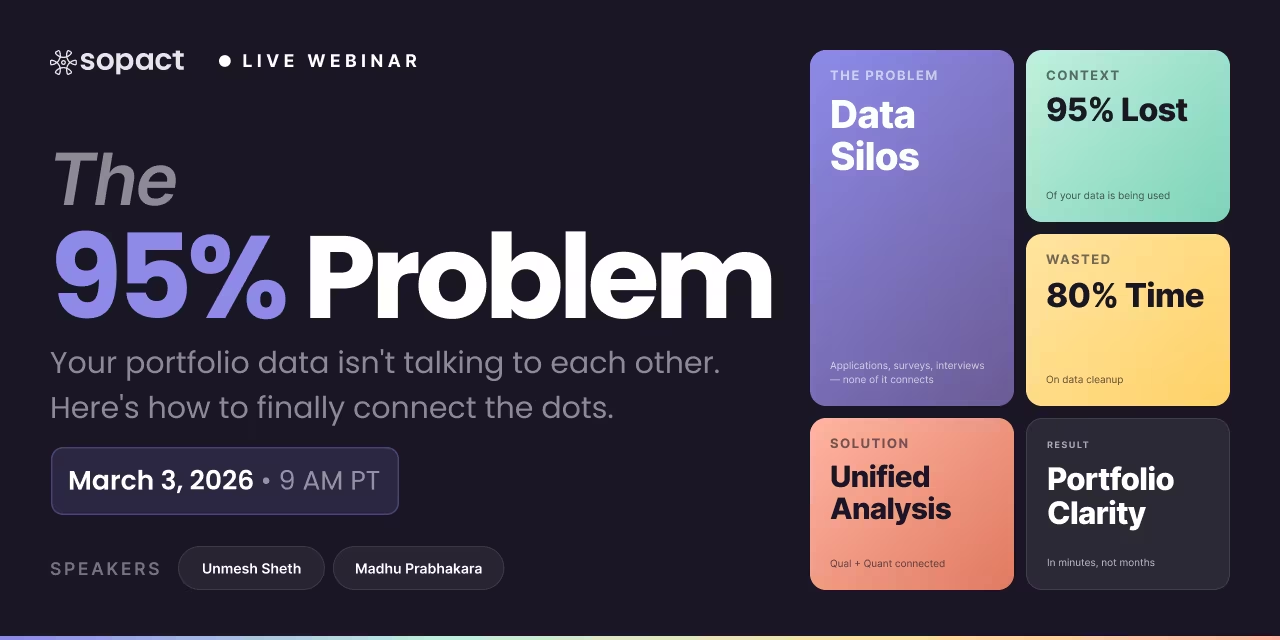

New webinar on 3rd March 2026 | 9:00 am PT

In this webinar, discover how Sopact Sense revolutionizes data collection and analysis.

In September 2000, world leaders gathered at the United Nations and agreed on a bold experiment: eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to guide global action until 2015.

The goals were simple and powerful:

For the first time, governments, donors, and NGOs aligned around a shared set of priorities. And there were successes. Global poverty dropped by more than half between 1990 and 2015. Primary school enrollment rates soared in low-income countries. Access to lifesaving HIV treatment expanded dramatically.

But as 2015 approached, cracks became visible.

The MDGs focused heavily on developing countries, often framing progress as an aid relationship between “North and South.” Yet global challenges—from climate change to inequality—were not confined to the Global South.

MDGs were negotiated largely by UN experts and government representatives. Communities most affected by poverty and inequality often had little say in shaping the goals.

While important, the MDGs left gaps. For example, peace, justice, and governance were barely mentioned. Economic growth was implicit but not central. Environmental sustainability was reduced to a single goal, overlooking the climate crisis already unfolding.

A UN review in 2013 summarized it bluntly: the MDGs helped focus attention, but they were “too narrow to drive the systemic change the world needs.”

In 2015, after three years of negotiations that included governments, civil society, businesses, and millions of citizens, the UN adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—anchored by 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

This was not just an update; it was a paradigm shift.

Unlike the MDGs, the SDGs apply to all countries—rich and poor alike. Climate action, inequality, sustainable consumption, and responsible production require global participation.

The process of drafting the SDGs included voices from around the world, including grassroots organizations, youth groups, and businesses. The goals reflect collective priorities rather than top-down targets.

Where the MDGs had 8 goals, the SDGs have 17, covering poverty, health, education, gender, environment, economic growth, innovation, governance, and peace. This recognizes that progress in one area depends on progress in others.

Each SDG comes with detailed targets and indicators, allowing countries to track progress more rigorously. And the design acknowledges interconnection: for example, improving education (SDG 4) is tied to gender equality (SDG 5), decent work (SDG 8), and reduced inequalities (SDG 10).

The move from MDGs to SDGs wasn’t cosmetic—it was recognition that the world had changed.

As one African minister put it during the negotiations:

“The MDGs were goals for us. The SDGs are goals with us.”

Under the MDGs, health was split into three vertical goals: child mortality, maternal health, and HIV/AIDS. This helped mobilize billions in funding and save millions of lives.

But health systems remained fragile. Ebola’s outbreak in West Africa (2014) showed that siloed health interventions without strong systems left countries vulnerable.

The SDGs reframed health under a broader “Good Health and Well-Being” goal, covering everything from universal health coverage to mental health to pandemic preparedness. It reflected a recognition that resilience, not just disease-specific progress, was critical.

For nonprofits, the shift means moving beyond single-issue projects to demonstrate how their work connects to systemic outcomes. A literacy NGO, for example, can now position its work not just under SDG 4 (Education), but also SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

For funders, the SDGs offer a common language. They make it possible to compare impact across sectors and geographies, fostering collaboration instead of isolated investments.

For communities, the SDGs offer recognition that their realities—be it access to clean energy, decent jobs, or justice—are part of a global agenda, not local afterthoughts.

The world shifted from MDGs to SDGs because solving poverty alone was no longer enough. The 21st century demands integrated, inclusive, and universal goals that recognize the complexity of human and planetary well-being.

The MDGs taught us the power of shared focus. The SDGs remind us that focus must be broader, deeper, and owned by all.

Or as one UN negotiator said in 2015:

“The MDGs asked what we could achieve in 15 years. The SDGs ask how we will live together for generations.”