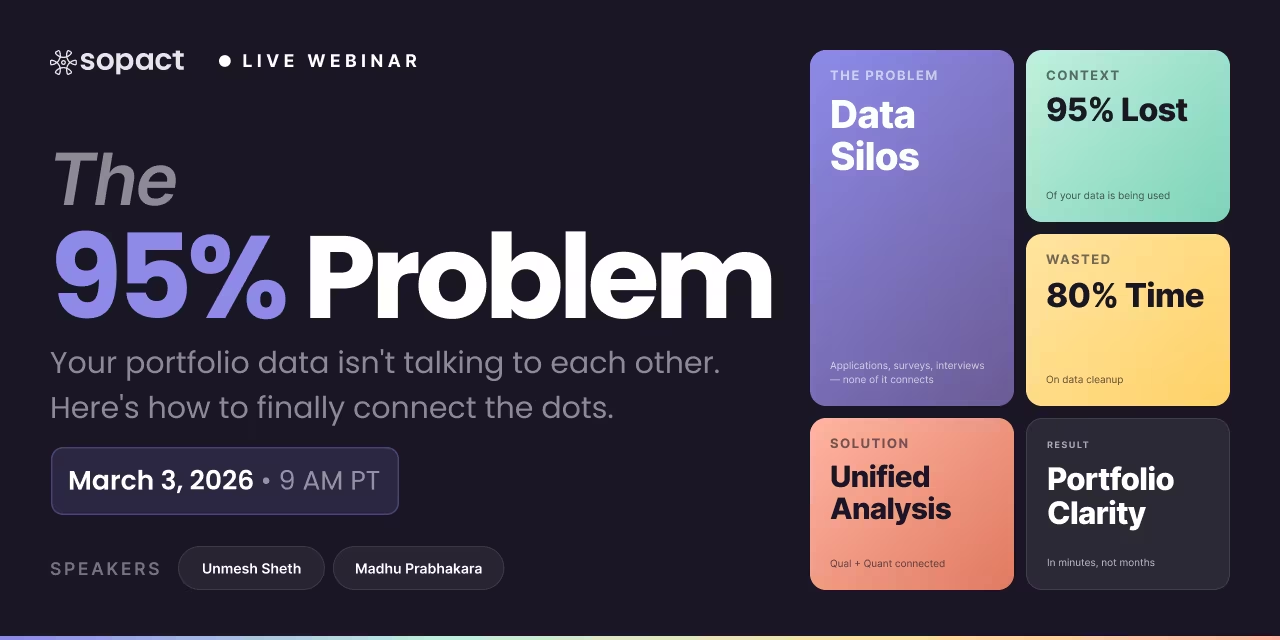

New webinar on 3rd March 2026 | 9:00 am PT

In this webinar, discover how Sopact Sense revolutionizes data collection and analysis.

Master program evaluation with proven methods, assessment frameworks, and outcome tracking tools.

You launched a program to change lives. You designed activities, recruited participants, tracked attendance, and collected surveys. Twelve months later, a funder asks a simple question: did it work?

And you realize you can't answer with confidence.

📌 IMAGE 1 PLACEMENT: program-evaluation-fragmented-vs-unified.pngPlace after this paragraph, before "This isn't a knowledge problem..."

This isn't a knowledge problem. You understand program evaluation. You know the difference between formative and summative evaluation. You can explain a logic model. The problem is architectural: your surveys live in Google Forms, your interview notes in Word documents, your metrics in Excel spreadsheets, and your annual reports in PowerPoint. When evaluation time arrives, you spend 80% of your effort cleaning and reconciling fragmented data — and only 20% actually analyzing what happened.

Traditional program evaluation treats assessment as a year-end compliance exercise. Teams wait until the program cycle ends to discover that critical baseline data was never collected, participant IDs don't match across surveys, and qualitative feedback sits in filing cabinets disconnected from quantitative outcomes. The evaluation becomes an autopsy — confirming what went wrong after it's too late to fix anything.

Effective program evaluation isn't a retrospective exercise. It's a continuous learning system built into your operations from day one. When your logic model connects directly to your data systems and evidence flows in real time, you shift from proving impact after the fact to improving outcomes while participants are still in your program.

That shift — from months of manual data reconstruction to real-time evaluation intelligence — is the difference between organizations that merely report on their programs and organizations that actually improve them.

📌 HERO VIDEO PLACEMENT: Place here, after the introduction, before the definition section.

<!-- HERO VIDEO: Place after introduction --><!-- Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXHuBzE3-BQ&list=PLUZhQX79v60VKfnFppQ2ew4SmlKJ61B9b&index=1&t=7s -->

Program evaluation is the systematic collection and analysis of information about a program's activities, characteristics, and outcomes to make judgments about effectiveness, improve program delivery, and inform decisions about future programming. It answers three core questions: Did we do what we said we'd do? Did participants change as intended? Can we attribute those changes to our program?

Unlike academic research focused on producing generalizable knowledge, program evaluation prioritizes actionable intelligence for specific stakeholders making specific decisions about specific programs. A workforce training organization doesn't need to know whether job training works in general — it needs to know whether this cohort's specific curriculum components drove measurable employment outcomes for their participants.

Program evaluation is systematic, meaning it follows a planned and structured process rather than ad hoc data gathering. It is evidence-based, relying on empirical data rather than assumptions or anecdotes. It is utilization-focused, designed to produce findings that stakeholders will actually use to make decisions. And it is context-specific, recognizing that a program's effectiveness depends on who it serves, how it's delivered, and the environment in which it operates.

The field has evolved significantly since the mid-20th century. Early approaches focused narrowly on whether programs achieved pre-defined objectives. Modern program evaluation embraces multiple methods, stakeholder perspectives, and evaluation purposes — recognizing that different questions require different evaluation designs, and that the most valuable evaluations combine quantitative measurement with qualitative understanding.

Understanding the different types of program evaluation helps you match evaluation design to the decisions you need to make. Each type answers different questions and serves different audiences.

Formative evaluation is conducted during program development and implementation to improve design, delivery, and operations. It answers the question: "How can we make this better while we still can?" Formative evaluation is most valuable during pilot phases and early implementation when program teams can still adjust curriculum, delivery methods, dosage, and targeting based on emerging evidence.

A literacy program might use formative evaluation to test whether a new reading intervention module increases student engagement before rolling it out across all classrooms. The evaluation reveals that the module works well for third graders but confuses first graders — allowing the team to create age-appropriate adaptations before scaling.

Summative evaluation is conducted at program completion or at defined milestones to assess overall effectiveness and impact. It answers the question: "Did this work, and should we continue, scale, or terminate?" Summative evaluation provides accountability evidence for funders, boards, and external stakeholders making resource allocation decisions.

A job training program's summative evaluation might show that 72% of graduates secured employment within six months — compared to 38% for a comparison group — at a cost of $4,200 per employed participant. This evidence helps funders decide whether to continue investing and helps the organization benchmark against alternatives.

Process evaluation examines whether program activities were implemented as planned, with fidelity, and reached intended participants. It answers: "Did we execute properly?" Process evaluation is essential because even well-designed programs fail when implementation breaks down. If a mentorship program planned for weekly one-hour sessions but most mentors averaged only two sessions per month, outcome shortfalls reflect implementation failure rather than a flawed theory.

Outcome evaluation measures changes in participant knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviors, or life conditions that result from program activities. It answers: "What changed for the people we serve?" Outcome evaluation requires baseline data collected before participation, consistent tracking instruments, and — critically — unique participant identifiers that link activities to observed changes over time.

Impact evaluation determines whether observed outcomes can be attributed to the program rather than external factors. It answers: "Did our program cause this change?" Impact evaluation uses comparison groups, statistical controls, or qualitative causal analysis to isolate program effects from confounding variables. When a community health program shows improved nutrition outcomes, impact evaluation determines whether the program caused the improvement or whether broader economic conditions, seasonal food availability, or other interventions explain the change.

Cost-effectiveness evaluation compares program costs to outcomes achieved, answering: "Are we getting good return on investment?" By calculating cost-per-outcome (such as cost per job placement, cost per student reaching proficiency, or cost per life improved), organizations can compare the efficiency of different program models and make informed resource allocation decisions.

Concrete examples across sectors show how evaluation principles translate into practice. Each example illustrates how evaluation questions, methods, and data systems work together to produce actionable evidence.

A coding bootcamp for underserved youth aged 18-24 uses program evaluation to prove employment outcomes and improve curriculum design. The evaluation tracks 200 participants from enrollment through 12 months post-graduation using unique participant IDs that link demographic data, attendance records, skills assessments, qualitative interviews, and employment outcomes.

Evaluation questions: Which curriculum modules predict job placement? Do participants from different educational backgrounds require different support levels? What explains the gap between skills certification and actual employment?

Key findings: Participants who completed the interview preparation module had 34% higher employment rates than those who skipped it — regardless of technical skill scores. This revealed that technical training alone wasn't sufficient; soft skills and job search support were critical missing links. The program redesigned its curriculum to make interview preparation mandatory.

A nutrition education program serving 500 low-income families evaluates whether workshop attendance translates into sustained dietary changes and improved child health outcomes. The evaluation combines attendance tracking, pre/post dietary recall surveys, food security assessments, and six-month follow-up interviews.

Key findings: Families who attended 6+ sessions showed statistically significant improvements in fruit and vegetable consumption — but only when sessions included hands-on cooking demonstrations. Lecture-only sessions produced knowledge gains but not behavior change. The program shifted 60% of its sessions to demonstration-based formats and saw behavior outcomes improve by 45%.

An accelerator program for women entrepreneurs evaluates revenue growth, business survival rates, and job creation. The evaluation uses quarterly revenue data, annual survival tracking, and qualitative interviews exploring how mentorship influenced business decisions.

Key findings: Businesses whose founders received 20+ hours of one-on-one financial mentorship generated 2.3x more revenue at 24 months than those receiving only group workshops. However, qualitative interviews revealed that the critical factor wasn't financial knowledge transfer — it was confidence building. Founders reported that having a trusted advisor made them willing to pursue larger contracts and negotiate better terms.

A school district evaluates its after-school tutoring program across 15 schools by comparing standardized test score improvements between tutored and non-tutored students, controlling for baseline performance, attendance, and socioeconomic status.

Key findings: The tutoring program produced significant gains for students starting 1-2 grade levels behind but had minimal effect for students more than 3 grade levels behind — suggesting these students needed more intensive intervention. The district used these findings to create a tiered support system, routing severely behind students to specialized programs while continuing standard tutoring for moderate achievers.

A mental health organization evaluates its peer support program for adults with depression. The evaluation combines clinical depression scales (PHQ-9) administered at intake, 3 months, and 6 months with qualitative narratives from participants about their recovery experience.

Key findings: Quantitative data showed a 40% reduction in average PHQ-9 scores at 6 months. But qualitative analysis revealed something the numbers missed: participants consistently cited "feeling understood by someone with lived experience" as the most transformative element — not the structured curriculum content. The organization used this insight to invest more in peer facilitator recruitment and training rather than expanding its clinical programming.

Program assessment and program evaluation are often used interchangeably, but the distinction matters for organizations building learning systems rather than compliance rituals.

Program assessment is the ongoing, continuous monitoring of program implementation and participant progress. Think of it as vital signs monitoring — constantly tracking key indicators so you can intervene when something goes wrong. Assessment happens during the program, often multiple times per cohort, generating immediate feedback that informs program delivery while participants are still engaged.

Program evaluation is the comprehensive, systematic analysis of overall program effectiveness, typically conducted at defined intervals. Think of it as a full medical exam — thorough, rigorous, designed to answer whether the patient is fundamentally healthy and what long-term changes are needed.

The critical insight is that assessment feeds evaluation. Continuous assessment data becomes the raw material for comprehensive evaluation. Organizations that treat them as separate exercises end up scrambling to reconstruct program implementation history when evaluation time arrives. Organizations that integrate them — using the same data architecture, the same participant IDs, the same connected systems — have rich longitudinal data showing not just what outcomes occurred, but which activities and delivery approaches predicted those outcomes across different participant segments.

A workforce training program's formative assessment reveals in week 3 that a new instructor's module has significantly lower engagement scores than the same module taught by other instructors. Without continuous assessment, this quality issue would only surface in the summative evaluation months later — after an entire cohort experienced substandard instruction. With real-time assessment, the program director can observe the session, provide coaching, and protect participant outcomes before damage compounds.

Choosing the right evaluation methodology depends on your evaluation questions, available data, resources, and the level of rigor your stakeholders require.

Quantitative methods produce numerical data that can be statistically analyzed to identify patterns, test hypotheses, and measure the magnitude of program effects. Common quantitative methods in program evaluation include pre/post assessments measuring change in participant knowledge or skills, surveys using validated instruments with Likert scales, administrative data analysis tracking outputs and outcomes over time, and experimental or quasi-experimental designs comparing treatment and control groups.

Qualitative methods provide depth, context, and understanding of how and why programs produce their effects. They capture participant experiences, reveal unintended consequences, and explain the mechanisms through which change occurs. Common qualitative methods include individual interviews exploring participant experiences in depth, focus groups generating discussion among participants with shared experiences, case studies examining specific instances of success or failure, and document review analyzing program materials, meeting notes, and communications.

The most powerful program evaluations combine quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data tells you what happened and how much. Qualitative data tells you why it happened and what it means to participants. Together, they produce evaluation findings that are both rigorous and actionable.

A mixed-methods evaluation of a financial literacy program might show that average credit scores improved by 47 points (quantitative) while participant interviews reveal that the most impactful element was accountability partnerships with other participants (qualitative) — an insight no survey would have captured.

Your logic model isn't just a planning tool — it's your evaluation framework. When properly designed, every component in your logic model becomes an evaluation question. Inputs become "Did we secure and deploy resources as planned?" Activities become "Were interventions delivered with fidelity?" Outputs become "Did we reach intended scale and quality?" Outcomes become "Did participants change as expected?" And impact becomes "Can we attribute community-level changes to our work?"

When your logic model connects directly to your data systems, evaluation shifts from retroactive storytelling to continuous evidence generation. You're not reconstructing what happened — you're watching it unfold and intervening when the evidence shows your theory isn't holding.

Whether you're a nonprofit program manager, an education administrator, or a workforce development professional, these steps provide a practical framework for planning and executing effective program evaluation.

Begin by identifying who needs evaluation findings and what decisions those findings will inform. Funders want accountability evidence. Program staff want improvement intelligence. Participants want assurance that their time matters. Each stakeholder group shapes the evaluation questions, methods, and reporting formats.

Build or refine a logic model that articulates the causal pathway from inputs through activities, outputs, outcomes, and impact. The logic model makes your program theory explicit and testable. It defines what success looks like at each stage and identifies the assumptions connecting each link in the chain.

Select evaluation questions that matter most given available resources and decision timelines. Prioritize questions that will actually influence decisions. Choose appropriate methods — quantitative for measuring magnitude, qualitative for understanding mechanisms, mixed methods for comprehensive evidence. Define your comparison strategy: pre/post measurement, comparison groups, or dose-response analysis.

This is where most evaluations fail. Before collecting a single data point, establish unique participant IDs that will link every touchpoint — enrollment data, assessment scores, attendance records, qualitative feedback, and outcome measurements — to the same individuals over time. Design your data collection to be clean at source, meaning every piece of information connects to your logic model from day one.

Execute your data collection plan using consistent instruments at planned intervals. Collect baseline data before program participation begins. Track participation intensity, not just enrollment. Capture qualitative feedback at multiple points — not just at exit when participants have already disengaged. Ensure data quality through validation rules, deduplication, and real-time monitoring of response rates.

Analyze quantitative data to identify patterns, effect sizes, and statistical significance. Analyze qualitative data to identify themes, mechanisms, and participant perspectives. Integrate both to create a comprehensive picture. Look for where findings converge (strengthening confidence) and diverge (revealing complexity). Always disaggregate by relevant subgroups — overall averages often mask critical differences in who benefits and who doesn't.

The purpose of program evaluation is not the report — it's the decision. Translate findings into specific, actionable recommendations. Present evidence to stakeholders in formats that match their decision-making needs. Build feedback loops so evaluation findings inform the next program cycle immediately, not twelve months later.

Education program evaluation applies these principles to schools, districts, universities, and educational nonprofits. The education sector has unique evaluation challenges: standardized testing provides readily available outcome data but captures only a narrow slice of student learning, multiple interventions operate simultaneously making attribution difficult, and academic calendars create natural evaluation windows.

Effective education program evaluation goes beyond test scores to measure student engagement, social-emotional development, teacher effectiveness, and long-term outcomes like college enrollment and career readiness. It requires tracking individual students across interventions and over time — connecting tutoring attendance to grade improvements to graduation rates to post-secondary success.

The most common mistake in education program evaluation is comparing program participants to general population averages rather than to similar students who didn't participate. A tutoring program's participants might show lower test scores than the school average — not because the program failed, but because the program serves the lowest-performing students who would have scored even lower without intervention.

Most organizations collect program data across multiple disconnected systems. Enrollment data lives in a CRM, attendance in spreadsheets, surveys in Google Forms, qualitative feedback in Word documents, and outcome data in separate databases. When evaluation requires connecting these sources, teams spend weeks or months manually reconciling participant records — often finding that IDs don't match, time periods don't align, and critical data points were never collected.

The standard evaluation cycle — plan program, deliver program, collect data at the end, analyze months later, report findings — means evidence arrives after the program cycle has ended, funding decisions have been made, and the next cohort has already started. Evaluation becomes a backward-looking accountability exercise rather than a forward-looking learning tool.

Organizations report "served 2,000 participants" and "delivered 500 workshops" as evidence of effectiveness. These are outputs — counts of what you did — not outcomes — evidence of what changed for participants. Without outcome measurement connecting activities to participant-level change over time, programs can operate indefinitely without evidence that they actually work.

Effective program evaluation requires solving the architectural problem — connecting data collection, analysis, and decision-making into an integrated system rather than treating them as separate activities.

Every participant gets a unique ID at enrollment that follows them through every interaction — baseline assessments, activity participation, mid-point check-ins, exit surveys, and follow-up measurements. This eliminates the reconciliation problem and enables longitudinal analysis showing how individual participants progress through the program.

Most organizations treat qualitative data (interviews, open-ended survey responses, case notes) and quantitative data (scores, counts, ratings) as separate streams requiring different tools and analysis approaches. Integrating both in a single system enables mixed-methods analysis that reveals not just what outcomes occurred but why they occurred and what they mean to participants.

Instead of waiting 12 months to discover a program isn't working, continuous evaluation surfaces disconnects between activities and outcomes in weeks — while there's still time to adapt delivery, reallocate resources, and improve results for current participants. This is the shift from evaluation as autopsy to evaluation as diagnostic tool.

Sopact's Intelligent Suite operationalizes these foundations. Intelligent Cell processes individual qualitative responses to extract outcome evidence. Intelligent Row summarizes each participant's journey from baseline through activities to outcomes. Intelligent Column identifies which program components predict which outcomes across cohorts. And Intelligent Grid generates comprehensive evaluation reports that map directly to your logic model structure — in minutes, not months.

Program evaluation is the systematic collection and analysis of information about program activities, characteristics, and outcomes to determine effectiveness and inform decisions. It matters because without evaluation, organizations invest resources in activities that might not produce intended outcomes. Evaluation provides the evidence needed to improve programs, demonstrate accountability to funders, and make informed decisions about which approaches to continue, modify, or discontinue. The shift from assumption-based to evidence-based program management is what separates high-performing organizations from those that repeat the same mistakes cycle after cycle.

The five main types are formative evaluation (improving programs during implementation), summative evaluation (assessing overall effectiveness at completion), process evaluation (examining whether activities were delivered as planned), outcome evaluation (measuring participant changes in knowledge, skills, behaviors, or conditions), and impact evaluation (determining whether observed changes can be attributed to the program). Most rigorous evaluations combine multiple types to answer different stakeholder questions — formative for improvement, summative for accountability, and impact for scaling decisions.

Program assessment is continuous, real-time monitoring during program delivery — tracking attendance, satisfaction, and short-term progress to catch problems early. Program evaluation is comprehensive, systematic analysis at defined intervals — determining overall effectiveness and whether outcomes justify continued investment. Assessment is like checking vital signs; evaluation is a full medical exam. The critical connection is that continuous assessment data becomes the raw material for comprehensive evaluation, but only when both use the same data architecture with unique participant IDs linking activities to outcomes over time.

Program outcomes are specific, measurable changes in participants' knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviors, or life conditions resulting from program activities. You measure outcomes by establishing baseline data before participation, assigning unique participant IDs that track individuals across time, collecting endpoint data using consistent instruments, and comparing changes while controlling for external factors. The most common mistake is confusing outputs (number served, workshops delivered) with outcomes (skills gained, employment secured). Outcomes require proving participant-level change, not just program-level activity.

Outputs are direct, countable products of program activities — number of people trained, workshops conducted, sessions completed — proving you delivered your program. Outcomes are changes in participant knowledge, skills, behaviors, or conditions — proving your program actually worked. The simplest test: if you can count it immediately without following up with participants, it's an output. If you need to track participant change over time, it's an outcome. A job training program's output is "trained 200 participants." Its outcome is "65% secured employment within six months at wages above $15/hour."

Your logic model is your evaluation framework. It defines what to measure at each stage, articulates the causal theory you're testing, and identifies the assumptions to validate. Every component becomes an evaluation question: Did we secure resources (inputs)? Were activities delivered with fidelity? Did we reach intended participants (outputs)? Did participants change (outcomes)? Can we attribute community changes to our work (impact)? Organizations that build logic models separately from evaluation end up retrofitting evidence to conclusions. Integrated approaches ensure evaluation tests the actual theory guiding program design.

The core steps are to engage stakeholders to define evaluation purpose and questions, describe the program using a logic model, focus the evaluation design by selecting methods and measures, build data architecture with unique participant tracking before collecting data, gather credible evidence through systematic collection, analyze findings using both quantitative and qualitative methods, and use findings to inform decisions and improve programming. The critical insight most organizations miss is step 4 — building connected data systems before collecting data eliminates the 80% of evaluation time traditionally spent reconstructing fragmented evidence.

Technology transforms evaluation by maintaining unique participant IDs that link baseline data through activities to outcomes over time, enabling causal analysis impossible with aggregate metrics. AI-powered analysis processes qualitative feedback at scale, summarizes individual participant journeys, identifies which activities predict which outcomes, and generates reports mapped directly to logic model structure. The breakthrough isn't faster data collection — it's clean-at-source architecture where every data point connects to your evaluation framework from day one, eliminating the manual reconciliation that consumes most evaluation effort.

Summative evaluation assesses a program's overall effectiveness, merit, and worth at the conclusion of a program cycle or at major milestones. It provides the evidence stakeholders need to decide whether to continue, expand, reduce, or terminate a program. Summative evaluation typically examines the full range of intended outcomes, calculates cost-effectiveness ratios, and compares results against benchmarks or comparison groups. While formative evaluation asks "how can we improve?", summative evaluation asks "did this work, and was it worth the investment?"

The purpose of program evaluation is to generate actionable evidence that improves programs, demonstrates accountability, and informs strategic decisions. Evaluation serves three overlapping purposes: improvement (identifying what works and what doesn't so programs can adapt), accountability (demonstrating to funders, boards, and communities that resources produce results), and knowledge generation (building understanding of which approaches work for which populations under which conditions). The most effective evaluations serve all three purposes simultaneously by embedding evaluation into ongoing program operations rather than treating it as an add-on reporting requirement.

Program evaluation doesn't have to be a year-end scramble. When data collection, analysis, and decision-making connect through a unified architecture with participant-level tracking, evaluation becomes what it should be: a continuous learning system that improves outcomes for every participant in every cohort.

Ready to see how continuous evaluation works in practice?