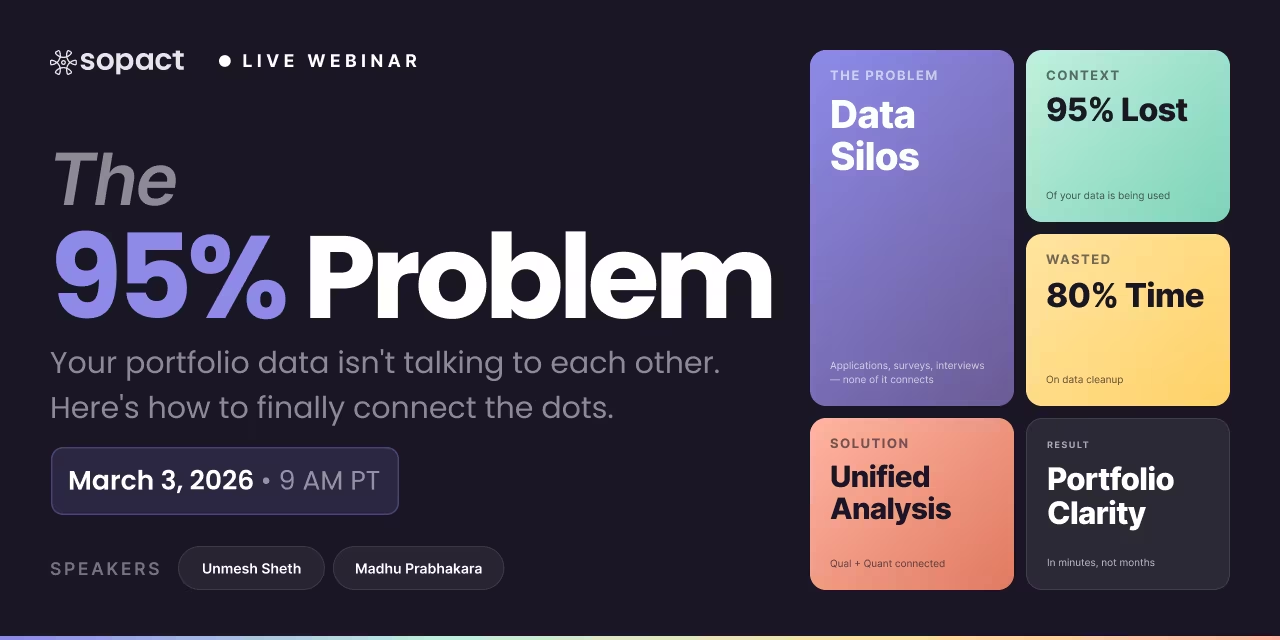

New webinar on 3rd March 2026 | 9:00 am PT

In this webinar, discover how Sopact Sense revolutionizes data collection and analysis.

Longitudinal studies track participants across time to prove lasting impact. Learn design principles, real examples, advantages vs disadvantages, and how.

You're collecting snapshots when you should be capturing journeys.

A survey here. An interview there. A report at year-end. But when funders ask the question that matters most—"Did your program actually make a difference?"—you're left guessing.

A longitudinal study changes everything. It tracks the same participants across multiple time points, connects pre/mid/post assessments automatically, and reveals outcome trajectories instead of isolated data points.

The Framingham Heart Study has tracked cardiovascular health since 1948—over 75 years of continuous longitudinal research spanning three generations. The Harvard Study of Adult Development has followed participants for more than 80 years. These landmark longitudinal studies transformed medicine and psychology by proving what cross-sectional snapshots never could.

Now the same powerful methodology is accessible for program evaluation, nonprofit impact measurement, and social research—without the massive infrastructure traditionally required.

This guide gives you everything you need to design, implement, and analyze a longitudinal study that proves real change over time.

A longitudinal study is a research design that involves repeated observations of the same participants over an extended period of time. Unlike cross-sectional studies that capture a single snapshot, a longitudinal study tracks how variables change, develop, and interact across weeks, months, years, or even decades.

The defining characteristics of a longitudinal study include:

Same participants tracked over time. A true longitudinal study follows the same individuals—not different people at each measurement point. This is what enables measurement of actual change within people.

Multiple data collection waves. A longitudinal study requires at least two time points, though most effective designs include three or more waves to capture trajectories rather than simple before/after comparisons.

Focus on change and development. The purpose of longitudinal research is measuring trajectories and patterns of change, not just static endpoints.

Temporal ordering established. Longitudinal studies can demonstrate that one thing happened before another—a necessary condition for establishing causality.

Longitudinal studies are used extensively in medicine, psychology, sociology, education, and increasingly in program evaluation and impact measurement. They provide the strongest observational evidence for understanding cause-and-effect relationships.

Longitudinal research takes several forms, each suited to different research questions and resource constraints. Understanding these types helps you choose the right longitudinal study design for your needs.

A panel study follows the exact same individuals across all time points. This longitudinal study design provides the strongest evidence for within-person change because you're measuring the same people repeatedly.

When to use a panel study: When you need to track individual trajectories and understand how specific people change over time. Ideal for program evaluation where you want to prove that these particular participants improved.

Panel study example: A workforce development program tracks 200 participants from enrollment through 18-month follow-up, measuring skills, employment, and income at intake, graduation, 6 months, and 18 months post-program.

A cohort study follows a group defined by a shared characteristic or experience—such as birth year, program enrollment date, or exposure to an event. This type of longitudinal study samples from a defined group but may not track every individual.

When to use a cohort study: When comparing groups who share defining experiences, or when tracking how program modifications affect different enrollment cohorts.

Cohort study example: A public health initiative compares diabetes prevention outcomes across quarterly enrollment cohorts (Q1 vs. Q2 vs. Q3) to assess whether program improvements produced better results.

Prospective longitudinal studies collect data in real-time as participants move forward through the study period. You design the study, enroll participants, and collect data at planned intervals.

Retrospective longitudinal studies analyze data that already exists—historical records, administrative databases, or previously collected research data—to identify patterns over time.

DimensionProspective StudyRetrospective StudyData collectionReal-time, plannedHistorical, existingControl over measuresHighLimited to what was collectedCostHigherLowerTime to resultsLongerFasterRecall biasMinimizedMay be present

Understanding the difference between a longitudinal study and a cross-sectional study is fundamental to choosing the right design.

A cross-sectional study captures data from different people at a single point in time—like a photograph. It shows what exists at one moment but cannot demonstrate change or causation.

A longitudinal study tracks the same people across multiple time points—like a time-lapse video. It reveals how individuals and variables change over time.

The critical limitation of cross-sectional data: When you survey different participants at intake and exit, you're comparing different people. You cannot know whether any individual actually changed. A longitudinal study solves this by tracking each participant's actual trajectory.

Like any research design, a longitudinal study has both significant strengths and important limitations to consider.

Establishes temporal sequence. A longitudinal study shows what happened first, enabling stronger causal inference. You can demonstrate that program participation preceded outcome improvement.

Measures within-person change. Unlike cross-sectional comparisons of different people, a longitudinal study reveals how each individual actually changed over time.

Identifies developmental trajectories. Longitudinal research shows not just endpoints but pathways—who improves quickly vs. slowly, who sustains gains vs. regresses.

Reduces recall bias. By collecting data prospectively at each time point, a longitudinal study avoids the errors that occur when participants try to remember past experiences.

Provides richer causal evidence. The Framingham Heart Study established smoking as a cardiovascular risk factor precisely because longitudinal tracking could show that smoking preceded heart disease—something cross-sectional data couldn't prove.

Participant attrition. People drop out of longitudinal studies for many reasons—they move, lose interest, become unreachable, or die. High attrition threatens validity if those who leave differ systematically from those who remain.

Time and cost intensive. A longitudinal study requires sustained investment across the full study period. Results take longer to materialize than cross-sectional research.

Potential for testing effects. Repeated measurement can change participant behavior. Someone surveyed about exercise habits might start exercising more simply because they're being asked about it.

Instrument consistency challenges. Maintaining identical measures across years or decades is difficult. If questions change, longitudinal comparisons become invalid.

Cohort effects may confound results. A longitudinal study of one generation may not generalize to other generations who experienced different historical contexts.

These real-world longitudinal study examples demonstrate how organizations implement different designs to answer questions about change over time.

The Framingham Heart Study (1948–present): Perhaps the most famous longitudinal study in history, Framingham has tracked cardiovascular health across three generations for over 75 years. This longitudinal research established the concept of "risk factors" and identified smoking, cholesterol, and blood pressure as cardiovascular threats—knowledge that has saved millions of lives.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development (1938–present): One of the longest longitudinal studies of human development, tracking the same individuals for over 80 years. This longitudinal study revealed that strong relationships—not wealth or fame—are the strongest predictors of healthy aging.

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study (1972–present): This New Zealand longitudinal study has followed over 1,000 individuals from birth, producing groundbreaking findings on mental health, aging, and the long-term effects of childhood experiences.

Youth Technology Training (Panel Study)

A nonprofit tracks 150 young adults through a 12-month technology skills program using 4 waves: intake, mid-program (6 months), exit (12 months), and follow-up (18 months). They measure coding test scores, confidence assessments, job placement, and salary data.

Why longitudinal: Cross-sectional exit data would miss whether skills translate into sustained careers. The 18-month follow-up reveals who maintains employment and who needs continued support.

Diabetes Prevention Cohort Study

A public health agency enrolls new cohorts quarterly into a diabetes prevention program, tracking each cohort through identical 12-month protocols. They compare A1C levels, weight, physical activity, and dietary patterns across cohorts.

Why longitudinal: Comparing cohorts reveals whether program improvements between quarters actually produce better health outcomes. This longitudinal study design shows not just end results but pace of change.

College Scholarship Panel Study

A scholarship fund supports 300 low-income students from high school through college graduation—a 6-year panel study combining annual surveys, administrative records (transcripts, financial aid), and semi-annual interviews.

Why longitudinal: The extended timeline captures the full student journey. Linking surveys with transcripts shows how financial support, academic performance, and wellbeing interact over time.

Here's why most organizations can't conduct effective longitudinal studies: the matching problem.

People change email addresses. They spell their names differently. They use nicknames. Your intake survey has "Sarah Johnson." Your 6-month survey has "S. Johnson." Your interview consent form shows "sarah.j.2024@gmail.com."

Common approaches that fail:

❌ Asking participants to remember a code. Nobody remembers the code. Response rates plummet. Those who do remember often mistype it.

❌ Manual matching after data collection. By the time you realize matching is needed, it's too late. Staff spend weeks on spreadsheet archaeology. Error rates exceed 15%.

❌ Relying on email addresses as identifiers. Emails change. Participants use different emails for different surveys. No single identifier persists.

The result: Fragmented longitudinal data, broken connections, and outcomes you can't actually prove when funders ask hard questions.

Sopact Sense eliminates fragmentation through a fundamentally different approach to longitudinal research.

From the very first touchpoint, every participant receives a unique identifier. Not a code they have to remember—an ID that lives in the system and follows them automatically across every interaction.

Step 1: Assign Unique ID at First ContactWhen a participant enters your program, Sopact Sense creates a persistent Contact record with a unique identifier.

Step 2: Auto-Link All Data to That IDEvery subsequent interaction connects automatically—pre-survey, mid-program interview, post-assessment, 6-month follow-up, uploaded documents. No manual matching required.

Step 3: Track Trajectories Across TimeWith connected data, you can analyze individual participant journeys, cohort patterns, change trajectories for any variable, and attrition patterns.

Step 4: AI-Powered AnalysisSopact's Intelligent Suite analyzes change patterns across all your longitudinal data—quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews together.

Participant attrition poses the greatest threat to longitudinal study validity. If those who drop out differ systematically from those who remain, your results are biased.

Reduce respondent burden. Shorter surveys completed more frequently often outperform long surveys with high dropout. Each additional question increases attrition risk.

Maintain contact between waves. Brief check-ins, program updates, or milestone acknowledgments keep participants engaged without requiring full survey completion.

Use multiple contact methods. Email, SMS, phone, and postal mail. Participants who stop checking email may still respond to text messages.

Implement automated follow-up workflows. Track who hasn't responded and send targeted reminders only to non-responders.

Provide self-correction links. When participants can update their own information, they stay engaged with the longitudinal study process.

When attrition occurs despite prevention efforts:

Document dropout patterns. Who left? When? What were their characteristics? This information helps assess whether bias exists in your longitudinal study.

Use appropriate statistical methods. Multiple imputation, maximum likelihood estimation, and growth curve modeling handle missing data more rigorously than simply excluding incomplete cases.

Report attrition transparently. Funders and stakeholders need to understand who was tracked and who was lost. Transparency builds credibility even when attrition is significant.

Ready to implement a longitudinal study? Follow this framework.

What change do you want to measure? Be specific. "Program effectiveness" is too vague. "Change in employment status from intake to 12 months post-program" is measurable.

Over what timeframe? How long does change take to occur? How long should you track to see if gains sustain?

For which participants? Define your study population clearly.

When will you collect data? Map waves to program milestones—intake, mid-program, exit, follow-up.

What will you measure at each wave? Core tracked variables should be identical across waves. Some questions may be wave-specific.

How will you maintain measurement consistency? Document your protocol. Use version control. Train staff on why consistency matters.

Set up participant tracking. Unique IDs assigned at first contact, automatic linking across waves.

Build survey instruments. Create forms for each wave. Test that data flows correctly.

Configure automated workflows. Reminder sequences, data quality checks, follow-up triggers.

Begin enrollment. Collect baseline data systematically.

Monitor response rates in real-time. Track who's responding. Address attrition early—don't wait until analysis.

Maintain data quality. Review incoming data for anomalies. Fix errors promptly.

A longitudinal study isn't just better methodology—it's the difference between reporting outcomes and proving them.

The organizations getting funding, demonstrating impact, and improving programs are those who can show trajectories, not snapshots. Individual journeys, not aggregate guesses. Sustained change, not single-point measurements.

Sopact Sense makes longitudinal research accessible. Unique IDs eliminate matching nightmares. Automated workflows prevent attrition. AI analysis surfaces patterns without manual coding.

Your next move:

🔴 SUBSCRIBE — Get notified when new videos drop

⬛ BOOKMARK PLAYLIST — Save the full course

📅 Book a Demo — See Sopact Sense in action

Let's turn your snapshots into stories.